TL;DR: The golden age of AI video has mastered the “look” of reality, but it has yet to learn the laws of reality. Without adhering to rigorous scientific principles, even the most photorealistic model remains a high-fidelity hallucination engine rather than a reliable world simulator. To bridge this gap, we introduce VideoScience-Bench: the first benchmark specifically designed to move beyond “physical commonsense” and evaluate undergraduate-level scientific reasoning in video models.

We also introduce VideoScience-Judge, a scalable VLM-as-a-judge pipeline that evaluates generated videos against rigorous scientific criteria. Correlation analysis shows that VideoScience-Judge achieves the strongest alignment with expert-rated rankings and best captures a video model’s scientific reasoning capability in comparison with existing benchmarks.

Video Model Reasoning and World Modeling

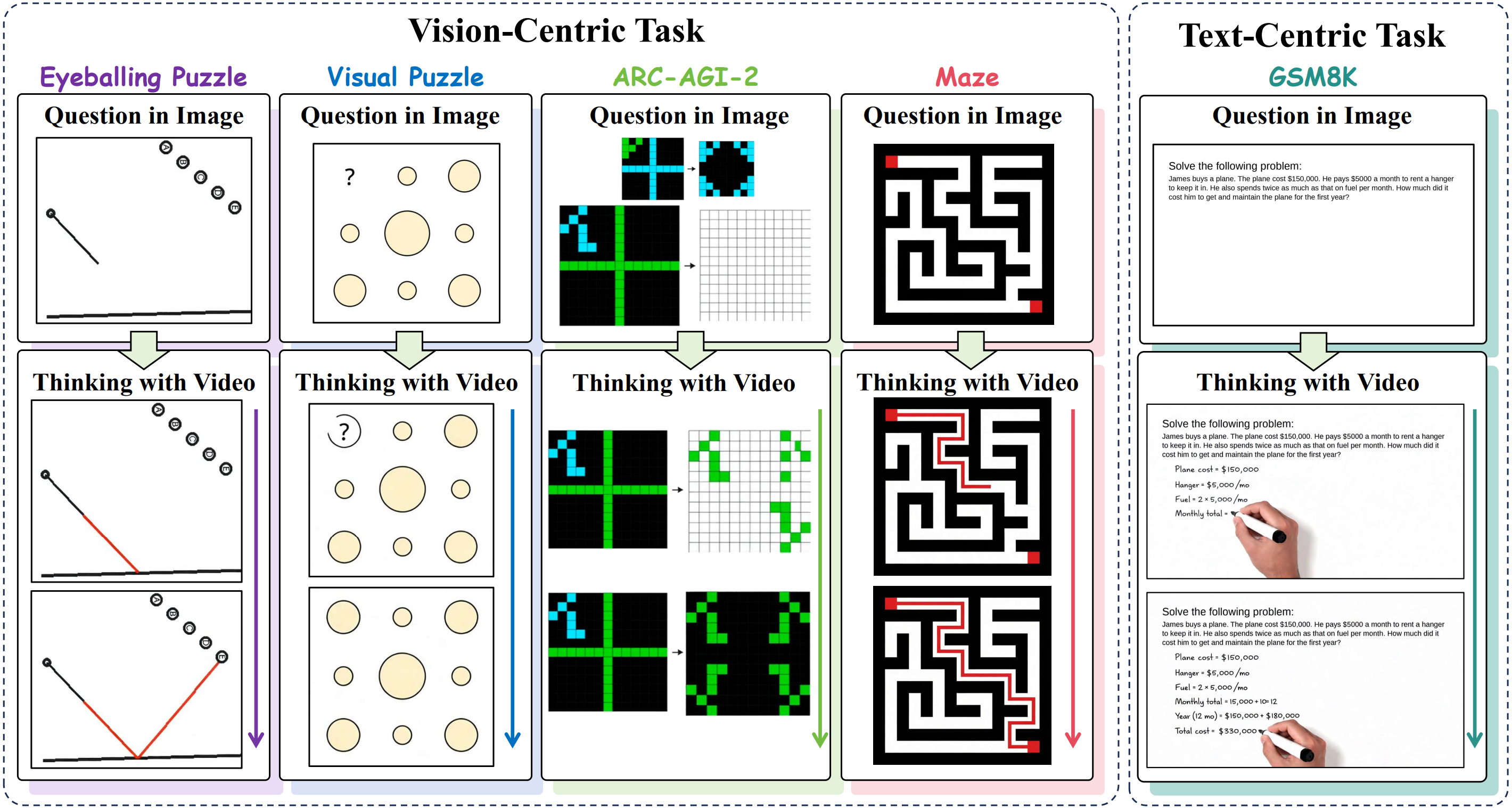

Spatial Reasoning and Puzzle Solving

This reasoning capability is most evident in spatial and puzzle-solving domains. Recent benchmarks, such as VR-Bench and VideoThinkBench, have demonstrated that video models can now solve mazes, mentally rotate objects, and handle spatial obstacle avoidance with surprising accuracy.

These achievements mark a pivotal shift: video models are no longer just generators, they’re becoming reasoners.

Simulation and Robotics Applications

In recent context of World Model Roadmap, WorldSimBench, video generation is increasingly framed as: implicit world model (physics + dynamics) + renderer (pixels). In this view, video models aren’t only content engines, they could be simulation engines. If the simulator is scientifically wrong, downstream systems trained on it can inherit those failures.

The stakes for scientific accuracy are highest in robotics, where models must evolve from simple visual generators into reliable world simulators. Industry leaders like 1X and NVIDIA are developing world models, such as 1X-WorldModel and Cosmos, that function as virtual simulators, leveraging raw sensor data to predict complex material interactions and envision potential futures. Because these systems generate the massive datasets used to train physical AI at scale, their adherence to scientific laws is a critical prerequisite for the safety and effectiveness of robots in the real world.

Scientific Reasoning as the Foundation of World Modeling

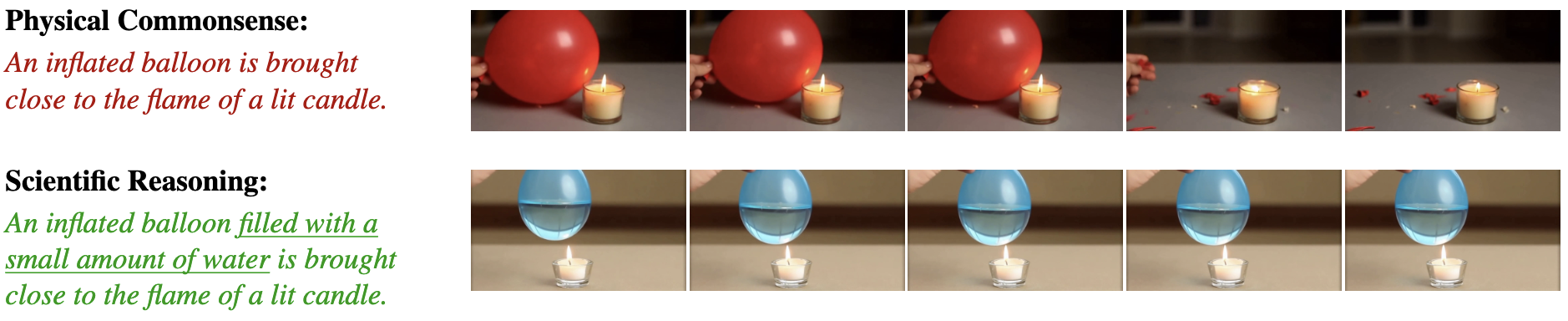

Spatial reasoning and puzzles are an important leap forward, but to be broadly useful, video models must evolve from Physical Commonsense (everyday intuition) to Scientific Reasoning (the rigorous application of multiple interacting principles).

Physical commonsense tests often ask: “Does this look plausible?”. On the other hand, scientific reasoning asks: “Does this obey the laws that govern the system, even when multiple concepts interact?”

The Current Gap: from Physical Commonsense to Scientific Reasoning

VideoScience-Bench

VideoScience-Bench is (to our knowledge) the first benchmark designed to evaluate whether video models can faithfully simulate multi-concept scientific phenomena, not just “look realistic.”

Unlike commonsense-based evaluations, each challenge in VideoScience-Bench requires:

- Multiple interacting concepts: Understanding how specific heat capacity and heat transfer principles work together to explain why a water-filled balloon doesn’t pop when exposed to flame

- Undergraduate-level knowledge: Spanning 103 concepts across 14 topics in physics and chemistry

- Complex reasoning: Moving beyond single-principle scenarios to cascading effects where second-order dynamics matter

Prompt: A teardrop-shaped piece of tempered glass is held at its bulbous head. Small pliers gently snip the thin tail end.

Expected: The entire drop explosively shatters into powder as internal tension is released.

Prompt: A clear plastic ruler is placed between two crossed polarizing filters and illuminated by a bright white light.

Expected: The stressed plastic causes rotation of the light's polarization plane in a wavelength-dependent way, yielding colored interference fringes.

Examples from VideoScience-Bench showing Sora-2 generated videos and expected phenomena.

Evaluation Metrics

We don’t just ask “Does the video look real?” We treat the video model as a simulation engine and evaluate it against five rigorous dimensions:

- Prompt Consistency: Does the experimental setup match the description?

- Phenomenon Congruency: Are the observed outcomes scientifically accurate?

- Correct Dynamism: Do motion and object interactions follow physical laws?

- Immutability: Do objects remain unchanged when they should?

- Spatio-Temporal Coherence: Are frame transitions smooth and temporally consistent?

This multidimensional framework enables us to pinpoint precisely where models succeed and where they fail, distinguishing between models that produce visually appealing but scientifically inaccurate videos and those that genuinely comprehend the underlying physics.

Key Findings: Scientific Understanding and Reasoning are still Lacking

Across seven state-of-the-art models Sora-2, Veo-3, Kling-v2.5-Turbo-Pro, Wan-2.5-T2V-Preview, Seedance 1.0 Pro, Hailuo 2.3, Ray2, we often see a recurring pattern:

While these models have mastered the aesthetics of reality, they often fail to grasp the physics of reality. We tested top models on VideoScience-Bench, a benchmark of 200 undergraduate-level science experiments, and found that even the best models frequently “hallucinate” physics.

The “Invisible Field” Failure: Great Visuals, Bad Physics

Generated Video

Reference Video

Prompt: A dry spaghetti stick is held at both ends and slowly bent until it breaks.

Expected: The spaghetti breaks into three or more pieces rather than two, because stress waves from the first fracture cause additional breaks before the fragments separate.

Generated Video

Reference Video

Prompt: A cart moves forward at a constant speed and launches a ball straight upward from its top."

Expected: The ball travels upward and then downward in a parabolic path, but lands back on the moving cart because both the ball and the cart have the same horizontal velocity.

Failure Examples on Violations of Phenomenon Congruency generated using Sora-2.

The Universal Failure: When No One Gets It Right

Generated Video

Reference Video

Prompt: A flask containing a yellow solution of glucose, sodium hydroxide, and the indicator indigocarmine is shown. The person lifts and gently shakes the flask.

Expected: The yellow solution rapidly shifts toward green as the flask is shaken, showing the indicator’s partial oxidation by oxygen introduced from the air. Continued shaking drives the oxidation further and the color moves from green to red. When agitation stops, dissolved glucose reduces the indicator and the solution relaxes back to yellow.

Generated Video

Reference Video

Prompt: A clear plastic water bottle has a small hole in its side, from which a smooth, laminar stream of water is flowing. A red laser pointer is aimed from the other side of the bottle, directly through the water and into the hole.

Expected: The laser beam enters the stream and becomes "trapped." It reflects repeatedly off the inner surface of the water stream, causing the entire parabolic arc of the falling water to glow red as if it were a fiber optic cable.

Failure Examples generated using Sora-2 on multi-concept scientific phenomena.

The “Complexity Collapse”: Failing the Setup

Generated Video

Reference Video

Prompt: Position a battery vertically on top of the three neodymium magnets so that the magnets contact the battery’s negative terminal. Place a heart-shaped copper wire so that it can touch both the top of the battery (positive terminal) and the sides of the magnets simultaneously.

Expected: When the copper wire touches both ends of the circuit, it begins to spin or move continuously, creating a small, self-turning “heart motor.

Generated Video

Reference Video

Prompt: A plastic film is placed between two crossed polarizing filters and illuminated by a white flashlight; the film is slowly twisted while being recorded.

Expected: The film’s birefringence splits light into components that interfere after passing through the analyzer. Rotation changes retardation, producing colored interference fringes dependent on polarization angle.

Failure Examples on Violations of Prompt Congruency generated using Sora-2.

While these AI models can render the “textures” of a laboratory—the glint of copper or the shimmer of a film—they fundamentally fail the “construction phase” of the experiment. In the first video, it renders a motor that cannot run because the model doesn’t understand that a circuit must be closed; it places the wire near the battery rather than connecting it to the terminals. While the prompt asks for the copper wire to touch both the positive terminal and the magnets, the model renders the wire floating or balanced on the “shoulders” of the battery.

In the second, it treats “birefringence” as a decorative skin on the plastic rather than an optical result of light passing through a specific sequence of filters. To see birefringence, the plastic must be sandwiched between two filters. Here, the film is held above two side-by-side filters that aren’t even overlapping.

Cross-Model Case Study: The Spectrum of Scientific Hallucination

Sora-2

Wrong Redox

Veo-3

Physical Morphing

Kling-v2.5

Object Hallucination

Qualitative comparison across models for "Electrolysis of Copper Sulfate" prompt.

While Sora-2 rendered realistic textures, it failed to adhere to the underlying electrochemical laws governing the electrolysis of copper sulfate. The model erroneously conflated oxidation and reduction at one electrode, leading to a nonphysical overproduction of solid copper and a failure to respect standard reaction kinetics.

Kling achieved high fidelity in lighting and fluid rendering, it fundamentally misunderstood the prompt’s physical setup. Instead of submerging copper wires acting as electrodes, the model hallucinated entire cylindrical batteries (or capacitors) and submerged them directly into the solution.

Veo failed to maintain the physical rigidity required for solid electrodes and ignored the chemical reaction entirely. The generated video exhibits “dream-like” physics where the copper rods morph, bend, and intersect with the glass beaker impossible ways, violating basic object permanence and solidity.

Ultimately, this experiment demonstrates that current video models operate on visual association rather than physical causation; while they can successfully render the di`stinct components of the setup—copper, glass, and solution—they fail to simulate the underlying electrochemical circuit, ignoring the flow of electrons and ions required to drive the specific redox reactions defined by the prompt.

Takeaways: The “Pretty but Wrong” Problem

A central takeaway is that today’s best video generators can be photorealistic and temporally smooth while still being scientifically incorrect.

That mismatch is exactly what VideoScience-Bench is designed to reveal:

- Models can imitate visual surface statistics

- Without reliably internalizing the causal structure and constraints of scientific systems

VideoScience-Judge: Scalable Expert-level Evaluation

Manual evaluation of scientific accuracy is labor-intensive and requires domain expertise. To enable scalable yet rigorous assessment, we developed VideoScience-Judge, a VLM-as-a-Judge framework that emulates expert evaluation through:

- Checklist Generation: An LLM generates a specific rubric for the prompt (e.g., “Check if the laser bends downward,” “Check if the liquid turns blue”).

- Evidence Extraction: We utilize computer vision tools (such as GroundingDINO, ByteTrack, and RAFT optical flow) to extract “hard evidence,” including tracking object trajectories and color changes, frame by frame.

- VLM Grading: A reasoning-capable VLM acts as the final judge, reviewing the checklist against the visual evidence to assign a score.

Our experiments demonstrate that this method achieves a correlation of 0.89 with human expert ratings, significantly outperforming other evaluation methods.

Qualitative Comparison: VideoScience-Bench vs. Baselines

| Evaluation Framework | Core Mechanism | Limitations on VideoScience-Bench |

|---|---|---|

| T2V-CompBench | Attribute Binding Checks for the presence and consistent binding of object attributes. | • Surface-Level: Focuses on static attribute correctness rather than dynamic scientific validity. • Physics Blind: Misses critical failures in temporal coherence, momentum, and physical plausibility. |

| LMArena-T2V | Crowdsourced ELO Aggregates human votes from a general user base. | • Visual Bias: Voters prioritize visual fidelity over logical correctness, often ignoring scientific inaccuracies. • Irrelevance: Most prompts test daily scenarios rather than scientific reasoning. |

| PhyGenEval (PhyGenBench) | Rule-Based / Binary Checks for discrete violations (e.g., “Did the object fall?”). | • Lack of Nuance: Fails to capture holistic physical realism like acceleration patterns, momentum, and causal relationships. • Rigidity: Binary judgment cannot evaluate the “cascading effects” of multi-concept phenomena. |

| VideoScore2 | General-Purpose VLM Trained on real-world prompts to assess “plausibility”. | • Everyday Bias: Prioritizes “looking plausible” (everyday common sense) over rigorous domain-specific physical laws. • Data Gap: Training data lacks complex scientific scenarios, causing it to accept scientifically inaccurate but visually “normal” videos. |

| VideoScience-Judge (Ours) | Evidence-Based VLM Uses domain-specific checklists + Computer Vision (CV) tools. | • Holistic Reasoning: Explicitly evaluates Phenomenon Congruency and Correct Dynamism using extracted key frames. • Expert Alignment: Achieves the highest correlation with human experts by grounding scores in concrete physical evidence. |

The Bottom Line

Modern models excel at producing high-quality, photorealistic, and temporally coherent videos that are visually stunning, VideoScience-Bench reveals fundamental limitations in their ability to comprehend complex scientific phenomena.

Among the evaluated models, Sora-2 and Veo-3 demonstrate notably stronger performance. These models show an emerging ability to handle multi-concept scenarios and maintain physical consistency, suggesting that the path toward scientifically literate video generation, while challenging, is not out of reach.

The path forward

Video models are at an inflection point. If we want them to become reliable world simulators, we need to measure and then train for scientific correctness. VideoScience-Bench provides a testbed to track this progress. Looking ahead, scientifically grounded video world models could:

- accelerate scientific discovery via accurate simulation

- enable safer and more capable robotics

- power education and training tools

- support rapid engineering prototyping and testing

We hope VideoScience-Bench helps push video models toward being not only compelling generators, but faithful simulators that can reason about the laws governing our world.

Get started

- GitHub: https://github.com/hao-ai-lab/VideoScience

- Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.02942

- Dataset: https://huggingface.co/datasets/lmgame/VideoScienceBench

- Leaderboard: https://huggingface.co/spaces/lmgame/videoscience-bench

Citation

@article{hu2025benchmarking,

title={Benchmarking Scientific Understanding and Reasoning for Video Generation using VideoScience-Bench},

author={Hu, Lanxiang and Shankarampeta, Abhilash and Huang, Yixin and Dai, Zilin and Yu, Haoyang and Zhao, Yujie and Kang, Haoqiang and Zhao, Daniel and Rosing, Tajana and Zhang, Hao},

journal={arXiv preprint arXiv:2512.02942},

year={2025}

}